Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven. Modernism is Mirrored

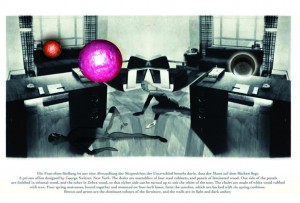

Anne-Mie. She reads a book called Art and Science of 1971 (Berlin, end of September 2009). One of the subtitles is “Modes of Thinking.” “Modes of Thinking” are actually her modes of working (and this is why I give this detail). They govern her manner. They drive her energy. Modernism is Mirrored: her “modes of thinking” are made into vision (and into a theory). As it is often Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven’s way of approaching her – her – themes (in the sense of her present and ardent issues), she combines, superimposes and transforms sources. In the case of this edition we are confronted with images of the 1935 issue of one of the most prominent annual yearbooks on interior design, Decorative Art, into which shadows of figurines of a handbook on sexual technique of 1966 are pasted; and one also notices colorful spheres, levitating in space. Quotes of the two volumes appear below the images and give some loose information of what may be seen above. In these pictures Van Kerckhoven lets ideas of thought collide. Their common ground is a certain trait of alienation caused by mechanization. The interiors formerly staged for magazine pictures (to promote furniture sales during Depression), were vertically mirrored by the artist. This act transforms them into pure fantasy, a double vision. (Modernist design was pure fantasy as it was developed to change living conditions by introducing mass-produced simplified forms, to rationalize not only private space subsequent to factory working units, but also behavior, even to improve health). Digitally morphed, the exsanguinous figurines inhabit these spaces like ghosts, performing the most human act (sex) in the most technical manner (one is instructed by the handbook to improve life – mainly – through a better technique, to say function – and functionalize the exchange of passion). However, one could believe that the idea of the liberated living (Siegfried Giedion, 1927) is a utopian, id est unfulfilled vision, if there were not these disturbing planet-like spheres. Introducing them into the scene, Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven renders homage to the most radical dissenter of occidental thought – Charles Fourier, the 18th century inventor of the phalanstère (a utopian building structure for cooperatives), advocator of the liberté amoureuse and first feminist. What Van Kerckhoven is appealed to is Fourier’s vision that well-being is reached as soon as love and attraction between the sexes is accepted not only in order to free development of the individual, but also to produce harmony instead of conflict. According to his vision, people should be seen equivalent to the globes of a planetary system which are held in balance by means of their passionate energy (Charles Fourier, Théorie des quatres mouvements, 1808). One is visually attracted by the gleaming spheres Van Kerckhoven assembled and which have a quite bodily appearance. (As kind of mutually agreed not only the pictures of this edition were mostly made by night, but also the text was then written, and probably the best time to look at the work will be in the dark…) Fourier’s proposal of the human liberation of the body is positively connotated and this is what the artist points to in particular by bringing orbs into play. The aura of orbic spheres, as explainable as they are, is introduced by the artist as interlink to remind us of a human harmonizing (and fervent) dimension which is lost when irrationality is buried under formalistic devices. Note also Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven’s selection of only representative interiors of living rooms and offices – no kitchen, no bedroom was chosen, no place where human interaction is normally done. However, in her trinity of modernism – sexual science – utopia, the latter seems most key to her understanding. Utopia as the land of vision and thought but not of realization, her oeuvre, again, provokes a mental collision. Her work is theory in visual terms, how fervent can theory still be?

S.N.